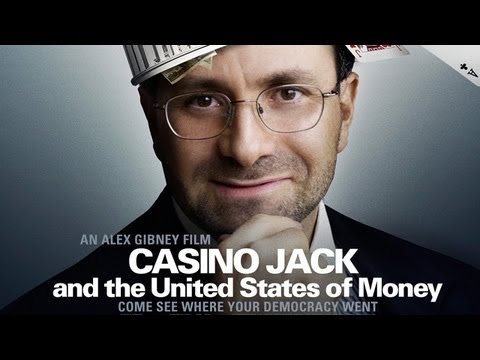

Much like his other available works, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and the recent Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer, filmmaker Alex Gibney explores wrongdoing in American government.

This time, Gibney shows how one sweet talking lobbyist went out of his way for a cause he believed him, turning congress into a lucrative business where votes were for sale to the highest bidder.

A Brief Timeline of Casino Jack and The United States of Money

The film begins by explaining how some floating Florida casinos were changing hands from wealthy Greek business Gus Boulis to Abramoff and Adam Kidan. Before long, Boulis is assassinated in his car by an alleged mob hit, this following a publicized altercation between the former and Kidan.

It is later revealed that the purchasing pair fraudulently fabricated a 23 million dollar wire transfer in order to secure a much larger loan in order to purchase the fleet of casino yachts, themselves floating money makers.

Gibney then takes us all the way back to the beginning, describing how Abramoff, the son of a well-to-do businessman, moved to Beverly Hills with his family. The young enterprising man soon manages some movie theatres, and discovers Topol’s performance as Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. Soon thereafter, he converts to Orthodox Judaism.

As he completed his university studies in the early 1980s, Abramoff becomes involved in the College Republican movement, along with like-minded individuals Grover Norquist and Ralph Reed. Together, the trio start engaging in activist activities aimed at exposing Democratic inadequacy, with the end goal of reaching a Republican House majority in later elections.

Gibney displays how the Abramoff-Norquist-Reed trio radically changed the College Republican organization, with Abramoff as the snake charmer, Norquist as the numbers man and Reed as the man of action.

As the 1980s progress, Abramoff makes more and more contacts within the government, having the ear of several well-established Republicans, finding himself having a seat at dinner with President Reagan at some fund raising functions.

A short amount of time is spent on how Abramoff and his friends tried to influence government into assisting an Angolan revolutionary, through an organization called Citizens for America. This later led to Abramoff producing a Hollywood action film called Red Scorpion, starring Dolph Lundgren. The film wasn’t very well received at the box office, and echoed the situation Abramoff had been trying to change in Angola.

The remainder of the documentary, a heavy dose of back-and-forth between organizations, shows exactly how Abramoff was instrumental in securing funds from one given group (say, for example, a First Nations tribe looking to influence Washington policies in their favor) in order to spread the wealth by convincing select members of Congress to vote in that given tribe’s favor.

This didn’t always work out for everyone, and soon proof of the large amounts being paid out for these “favors” began to surface, leading to a Senate sub-committee (headed by a pre-election John McCain) investigating allegations of bribery and unauthorized lobbying by way of gifts and unfounded business trips.

The film finally comes back full circle, with events leading back to Abramoff collaborating with Kidan in falsely securing the Floridian casino yachts from Boulis.

Money Definitely Talks in Casino Jack and The United States of Money

There’s a sickening feeling one gets while watching this documentary, that of becoming aware of just how much corruption exists in any organization, even one as legal as that of an elected body. Gibney got incredible access to several key players in the story, such as Congressman Bob Ney (who later served time for being involved in Abramoff’s fraudulent activities), Reed, Kidan, Norquist and Texas Congressman Tom DeLay, who you might have seen recently on Dancing with the Stars.

Ironically, one member involved in the scandal, a lobbyist named Neil Volz, comes off as being the only person interviewed to show any kind of remorse in the affair, while the rest use their political experience to downplay any guilt they may feel at what transpired.

Though Gibney details how all of these players financially benefited off the backs of others, most of those interviewed deftly deflect blame back onto Abramoff, as if they hadn’t had the slightest clue anything wrong had occurred.

Some of you may find Casino Jack and the United States of Money a little bit difficult to absorb. It is quite detailed and requires a modicum of knowledge about the American political system, awareness of the basic differences between Democratic and Republican values as well as a working understanding of the 1980s political landscape.

Should you lack in any of the above areas, trust in the fact that Gibney does most of the work for you. Failing to grasp the nuances might make this piece seem a bit bland and dry, however I can assure you that Gibney’s narrative is just as captivating as his previous work on the Enron scandal.

If you need a laugh after the credits roll, get yourself over to the extras, where an updated, tongue-in-cheek version of the “I’m Just a Bill” cartoon appears.

The Final Word on Casino Jack and the United States of Money

As far as documentaries go, this one does the job admirably, but is often too dense for any uninformed viewer to grasp most of the content without at least having a reference guide (or Wikipedia) handy too figured out who did what.

Despite said density, Gibney is arguably a worthwhile voice who exposes American corruption, and is unafraid to show elected officials’ true colors. For a similar experience, I urge you to check out his other documentaries, they are just as shocking.